This is a poster used for the application of 2019 ESRI Young Scholar Award. There are two projects included: one is to analyze spatial-temporal patterns of spruce budworm defoliation within plots in Québec, and another one is to determine the influencing factors on spruce budworm population dynamics (in progress).

Summary Report

Research Background

The spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana [Clem.]; SBW) is one of the most destructive insects in North America’s conifer forests. SBW outbreaks typically occur every 35 years, resulting in large-scale mortality and economic losses [1–3]. Effective management of SBW should account for the dynamics of stands and insect populations, especially during an outbreak initiation. On the other hand, Baskerville and MacLean [4] observed that SBW-caused tree mortality of balsam fir (Abies balsamea [L.] Mill.) had a strongly contagious spatial distribution. Given that tree mortality is strongly related to cumulative defoliation [5,6], a clustered spatial distribution of dead trees may reflect higher defoliation in those trees than in surrounding trees. However, no previous studies have determined spatial patterns of SBW defoliation among trees, and the spatial inter-relationships of defoliation levels of trees within a plot are not well understood.

Sub-project A

Study Description

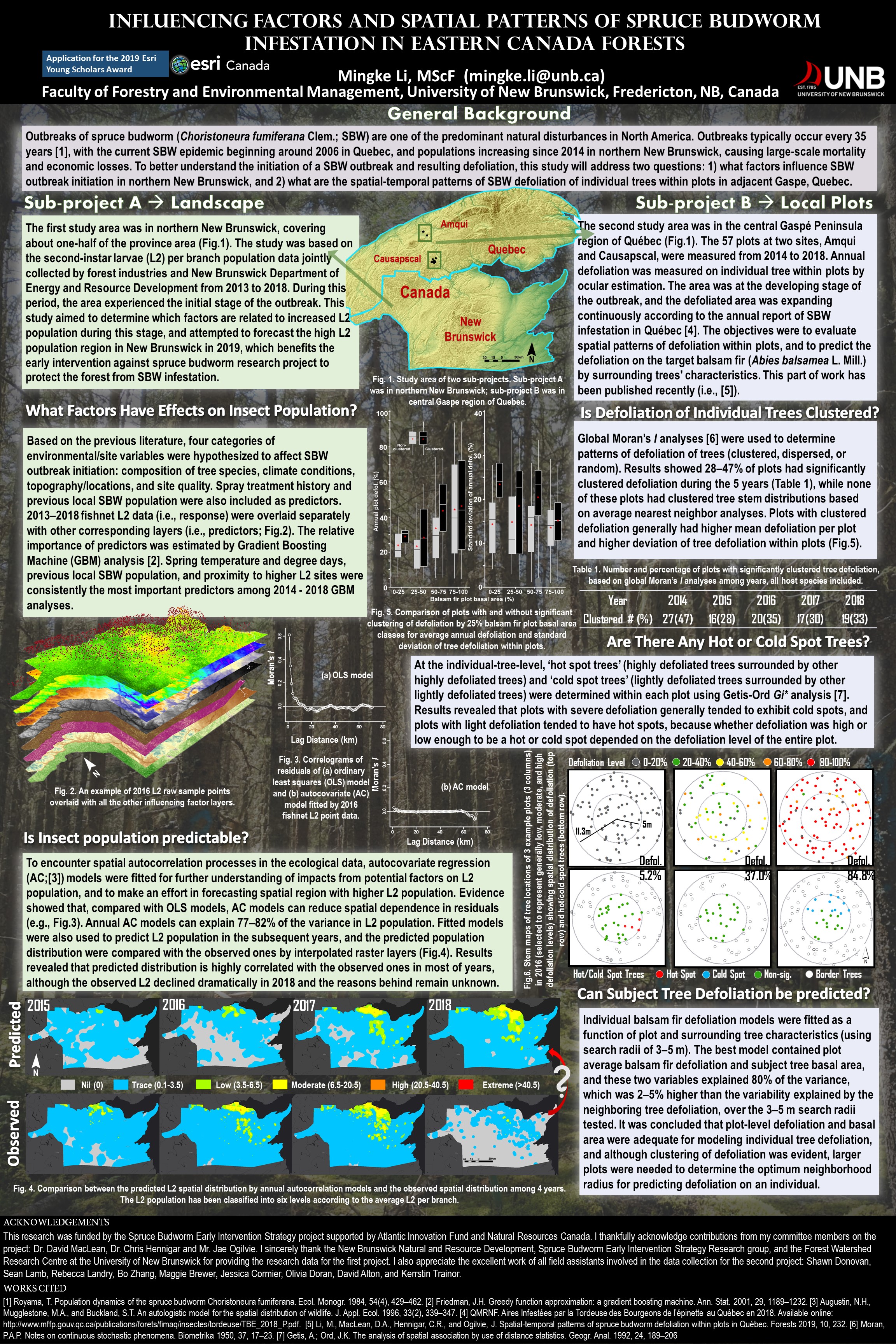

The first study area was in northern New Brunswick, covering about one-half of the province area. The study was based on the second-instar larvae (L2) per branch population data jointly collected by forest industries and New Brunswick Department of Energy and Resource Development from 2013 to 2018. During this period, the study area experienced the initial stage of the outbreak. The objective was to understand what environmental and endogenous factors influence high insect population levels during the outbreak initiation.

Methodology

Based on the previous literature [7–11], four categories of environmental/site variables were hypothesized to affect SBW outbreak initiation: composition of tree species, climate conditions, topography/locations, and site quality. Spray treatment history and previous local SBW population were also included as predictors. Raw L2 sample points from 2013 to 2018 were interpolated as raster by inverse distance weighted methods, then points at every 2km were extracted as systematic fishnet L2 points from each interpolated raster. The fishnet L2 data (i.e., response) were overlaid separately with other corresponding layers (i.e., predictors). The top three uncorrelated factors (r < 0.7), based on the Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) tests [12], were used to create autocovariate models for each year’s dataset, for further understanding potential influencing factors, and forecasting spatial distribution of higher insect population.

Autocovariate regression was adopted in the modeling to encounter spatial autocorrelation in such ecological data [13]. Ordinary least squares (OLS) models were also fitted as the contrast. Fitted autocovariate models were used to predict L2 population in the subsequent years, and the predicted population distribution was compared with the observed ones by interpolating raster layers.

Main Results

- According to the GBM tests, temperature and degree days in April and May, previous local SBW population, and proximity to higher L2 sites were consistently the most important predictors over the study years.

- Compared with OLS models, autocovariate models can reduce spatial dependence in residuals.

- Annual autocovariate models can explain 77–82% of the variance in L2 population.

- Predicted distribution is highly correlated with the observed ones in most of the years, although the observed L2 declined dramatically in 2018 and the reasons behind remained unknown.

Sub-project B

Study Description

The second study area was in the central Gaspé Peninsula region of Québec. The study plots at two study sites, Amqui and Causapscal, were measured over 5 consistent years (2014-2018). This study focused on SBW-caused current defoliation, which was measured on each individual tree by ocular estimation. The study area was at the developing stage of the outbreak, and the defoliated area was expanding continuously in Québec [14]. This study aimed to evaluate spatial patterns of defoliation within plots, and to predict the defoliation on the target balsam by surrounding trees’ characteristics. This part of the work has been published recently (i.e., [15]).

Methodology

Firstly, tree stem distributions of each plot were evaluated by average nearest neighborhood analysis, which set the baseline for the spatial autocorrelation analyses of defoliation. Following that, two quantitative indices were used to characterize spatial patterns of defoliation at the plot and tree levels: global Moran’s I and Getis-Ord Gi* analysis. Global Moran’s I estimated the intensity of spatial dependence for the entire plot and summarized it with a single value [16]. Getis-Ord Gi* analysis determined defoliation patterns of individual trees within each plot, and detected hot and cold spots in terms of tree defoliation [17]. A 5m buffer zone was used to compensate edge effects in each plot. To understand whether defoliation levels of individual balsam fir can be predicted by plot or surrounding-tree characteristics, nonlinear mixed effect regression models were fitted, with plots nested within years as random effects.

Main Results

- At the plot level, 28-35% of plots showed significantly clustered defoliation patterns from 2014 to 2018, while none of the plots have clustered tree stem distributions.

- Plots with clustered defoliation tended to have higher and less uniform defoliation among trees. Results suggested that spatial defoliation patterns resulted from uneven SBW pressure on trees, perhaps from oviposition site selection.

- At the tree level, plots with severe defoliation generally tended to exhibit cold spot trees, and plots with light defoliation tended to have hot spot trees, because whether defoliation was high or low enough to be a hot or cold spot depended on the defoliation level of the entire plot.

- Plot-level defoliation and basal area were adequate for modeling individual tree defoliation. Although clustering of defoliation was evident, larger plots were needed to determine the optimum neighborhood radius for predicting defoliation on an individual.

Benefits

Understanding the potential environmental and endogenous influence on SBW outbreak initiation can have major implications for forest management and sampling design. Particularly, forecasts of the region with high insect population levels in the subsequent year benefit the effectiveness of insecticide spray treatment. Understanding the spatial-temporal variability of SBW defoliation among trees within plots or stands is important for projecting impacts of outbreaks on forests using stand growth models. Such knowledge should also help improve the design of defoliation sampling techniques, forecasting defoliation at unsampled sites, and evaluating management alternatives [18,19]. Knowledge of tree-level variability of defoliation is also important for predicting the effects of defoliation using a tree-list stand growth model, which would use tree-based annual defoliation values (e.g., [20]).

References

- MacLean, D.A. Effects of spruce budworm outbreaks on the productivity and stability of balsam fir forests. For. Chron. 1984, 60, 273–279.

- Royama, T. Population dynamics of the spruce budworm Choristoneura Fumiferana. Ecol. Monogr. 1984, 54, 429–462.

- Chang, W.Y.; Lantz, V.A.; Hennigar, C.R.; MacLean, D.A. Benefit-cost analysis of spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana Clem.) control: Incorporating market and non-market values. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 93, 104–112.

- Baskerville, G.L.; MacLean, D.A. Budworm-caused mortality and 20-year recovery in immature balsam fir stands, Maritimes Forest Research Centre, Canadian Forestry Service, Fredericton, N.B., Canada. Inf. Rep. M-X-102. 1979. 56p.

- Erdle, T.A.; MacLean, D.A. Stand growth model calibration for use in forest pest impact assessment. For. Chron. 1999, 75, 141–152.

- Chen, C.; Weiskittel, A.; Bataineh, M.; MacLean, D.A. Even low levels of spruce budworm defoliation affect mortality and ingrowth but net growth is more driven by competition. Can. J. For. Res. 2017, 47, 1546–1556.

- Bouchard, M.; Auger, I. Influence of environmental factors and spatio-temporal covariates during the initial development of a spruce budworm outbreak. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 111–126.

- Su, Q.; MacLean, D.A.; Needham, T.D. The influence of hardwood content on balsam fir defoliation by spruce budworm. Can. J. For. Res. 1996, 26, 1620–1628.

- Hennigar, C.R.; MacLean, D.A.; Quiring, D.T.; Kershaw, J.A. Differences in spruce budworm defoliation among balsam fir and white, red, and black spruce. For. Sci. 2008, 54, 158–166.

- Hardy, Y.; Mainville, M.; Schmitt, D.M. Spruce budworms handbook: an atlas of spruce budworm defoliation in eastern North America, 1938-1980, USDA, For. Serv., Coop. State Res. Serv., Washington, D.C., 1986.

- Magnussen, S.; Boudewyn, P.; Alfaro, R. Spatial prediction of the onset of spruce budworm defoliation. For. Chron. 2004, 80, 485–494.

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232.

- Dormann, C. F.; Mcpherson, J. M.; Arau, M. B.; Bivand, R.; Bolliger, J.; Carl, G.; Davies, R. G.; Hirzel, A.; Jetz, W.; Kissling, W. D.; Ohlemu, R.; Peres-neto, P. R.; Schurr, F. M.; Wilson, R. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data : a review. Ecography (Cop.). 2007, 30, 609–628.

- QMRNF: Québec Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune. Aires infestées par la tordeuse des bourgeons de l’épinette au Québec en 2018. Available online: http://www.mffp.gouv.qc.ca/publications /forets/fimaq/insectes/tordeuse/TBE_2018_P.pdf (accessed on Oct 20, 2018).

- Li, M.; MacLean, D.; Hennigar, C.; Ogilvie, J. Spatial-Temporal Patterns of Spruce Budworm Defoliation within Plots in Québec. Forests 2019, 10, 232.

- Moran, P.A.P. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 1950, 37, 17–23.

- Getis, A.; Ord, J.K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 1992, 24, 189–206.

- MacLean, D.A.; Lidstone, R.G. Defoliation by spruce budworm: estimation by ocular and shoot-count methods and variability among branches, trees, and stands. Can. J. For. Res. 1982, 12, 582–594.

- Reed, D. D.; Burkhart, H. E. Spatial autocorrelation of individual tree characteristics in loblolly pine stands. For. Sci. 1985, 31, 575–587.

- Lamb, S.M.; MacLean, D.A.; Hennigar, C.R.; Pitt, D.G. Forecasting forest inventory using imputed tree lists for LiDAR grid cells and a tree-list growth model. Forests 2018, 9, 167.